An empty TextWrangler window

So far, we've discussed how to use the UNIX command line to filter and modify files. We've also discussed how to use the Python interactive interpreter to play around with Python expressions and statements. Our next task is to learn how to put a punch of Python expressions and statements in order, and put them in a file. This is what's known as a Python program or "script." (The words "program" and "script" sound scary and technical, but they're meant in senses of those word that you're already familiar with---"script" or "program" as in a list of things that you want to happen.)

In order to write scripts, we need to be able to make plain text files and upload them to the server where we're using Python. A "plain text" file is a file with text in it but no other weird formatting information, like you'd get with (e.g.) Microsoft Word. There are many text editors out there, with different benefits and drawbacks. I'm going to recommend that you use either TextWrangler (if you're on OS X) or NotePad++ (if you're on Windows).

In the following two sections, I'm going to show you how to use these text editors to edit a plain text file and upload them to the server.

First, install TextWrangler. Launch TextWrangler (from Launchpad or by finding it in your Applications folder). You'll see a window that looks like this:

An empty TextWrangler window

Type the following text into the window:

print "Hello there"Congratulations, you've just written a Python program! It's a very simple program---it only has one statement, which causes the string Hello there to be written to output.

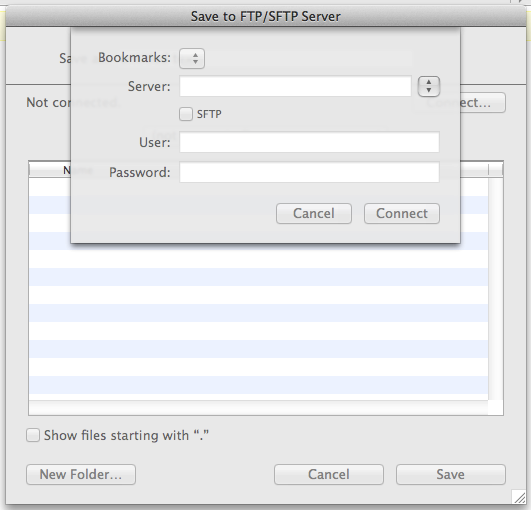

To save this file on the server, go to File > Save to FTP/SFTP Server.... You'll see a window that looks like this:

TextWrangler SFTP save dialog

(If you don't see that window exactly, you might have to click on the button labelled "Connect...")

In the text field labelled "Server", enter the name of the sandbox server for the class, followed by a colon, followed by the port number for the server, with no spaces in between, like so:

sandbox.server.hostname:12345(... replacing sandbox.server.hostname with the name of the class sandbox server, and 12345 with the port number. This is the same server and port that you've been using to log into the server with SSH and/or PuTTY.)

Click the box labelled "SFTP". In the "username" and "password" text fields, enter the username and password that you've been using to log into the server with SSH or PuTTY.

Now click "Connect."

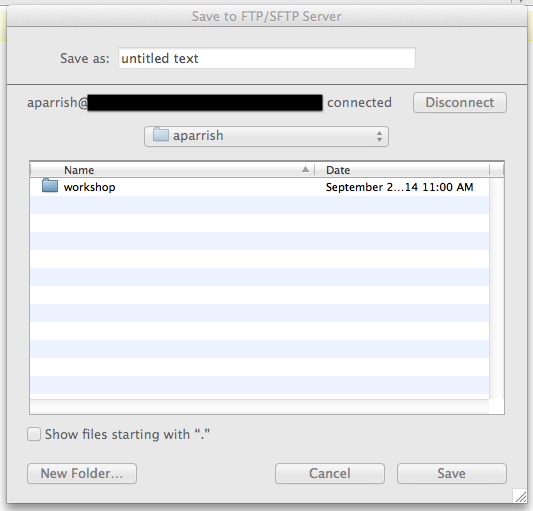

You should now see a window that looks like this:

TextWrangler SFTP save dialog, part 2

Fill in the "Save as:" text field with whatever you want to name the file, taking care to end the file with .py. (I suggest hello.py) In the portion of the window below, you can navigate which directory you want to save the file in on the server. Switch to the "workshop" directory and click "Save."

Congratulations! The file is now on the server. Now you can log into the server and run the Python program you just made. Log in using SSH and type this:

$ cd workshop

$ python hello.pyYou should see the string Hello there.

The next time you start TextWrangler, it should remember your settings. If you want to use TextWrangler to edit other files on the server, go to File > Open from FTP/SFTP server.... Connect with the same settings you used above. If you open a file with this interface, any changes you make will be saved to the file on the server.

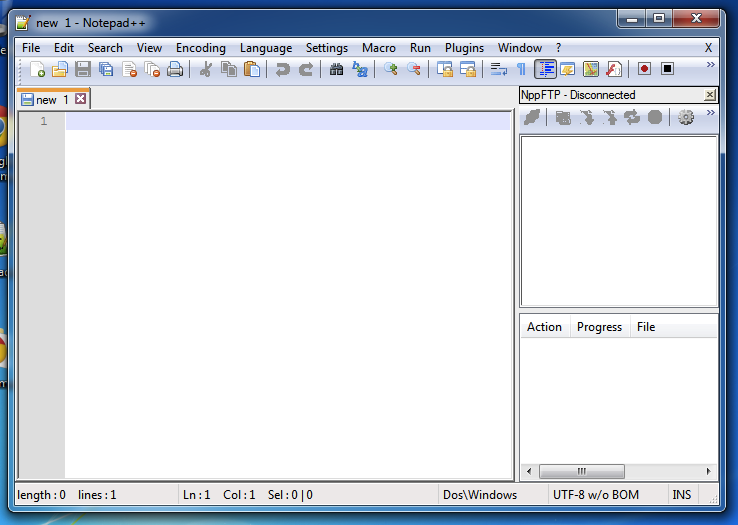

First, install Notepad++, then run it. (Double-click on the "Notepad++" icon on the desktop if you made a desktop shortcut, or find it in the Start menu.)

You'll see a screen like this:

New document with Notepad++

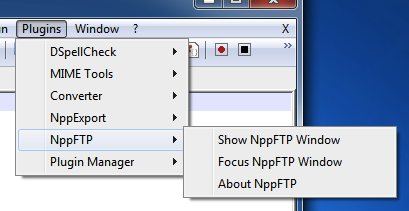

Now you need to create a new file on the server. To do this, you need to use a part of NotePad++ called "NppFTP." Activate it by going to "Plugins > NppFTP > Show NppFTP window."

Activating NppFTP

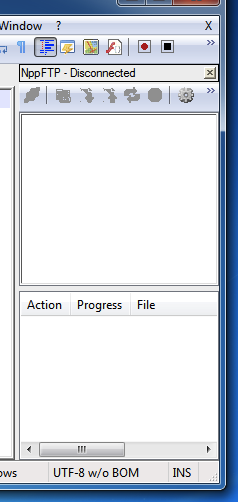

A panel that looks like this will appear in your Notepad++ window.

NppFTP panel

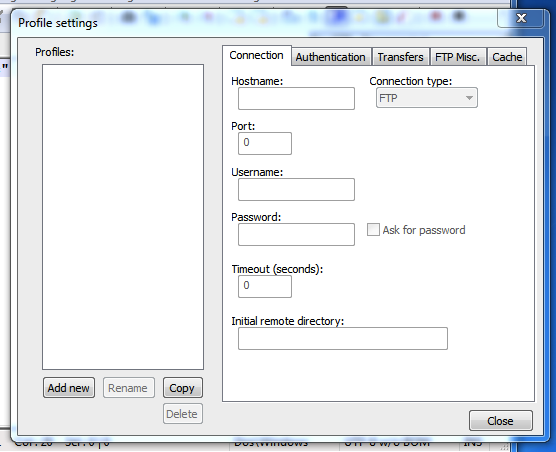

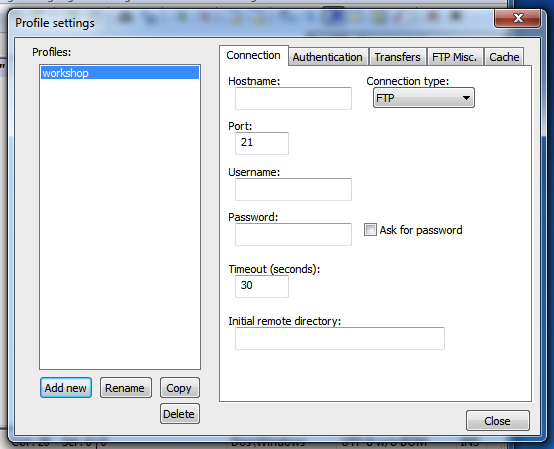

Click on the "Gear" icon in the upper right-hand corner and select "Profile Settings." You'll see a dialog box that looks like this:

NppFTP dialog

Click on "Add New" and choose a name (like "Workshop") as the profile name. Click "OK." Now you'll see a dialog that looks like this:

NppFTP dialog, step 2

This is where you'll enter information about the server. Follow these steps:

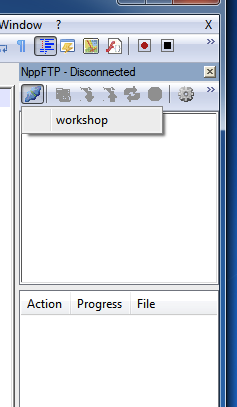

You'll be back in the main editor interface. Now click on the icon furthest to the left in the NppFTP interface. It should look like this:

Connecting with NppFTP

Select "Workshop" (or whatever you named the connection above). The status line above the icons should display "NppFTP - Connecting." If you get a dialog box asking to "trust the host key," click "Yes."

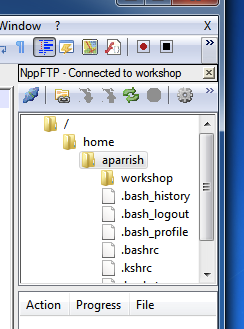

If you connected successfully, you should see something like this:

NppFTP connected!

Congratulations! It worked. If you didn't manage to connect, the panel will remain empty and eventually the status line will change back to "NppFTP - Disconnected." If this happens, go back into "Profile Settings" and ensure that you've entered everything correctly and try again.

Now that you're connected to the server, you can edit files on the server and create new files by selecting them in the NppFTP panel. First off, let's create a new file. In the panel, right-click on the directory labelled "workshop." (You should have created this directory in a previous chapter using mkdir while logged into the server.) Select "Create New File." In the dialog that pops up, enter hello.py. A new file called hello.py should appear in the panel. Double click on this file.

You're now editing a file called hello.py, and anything you type in the window will be saved to that file on the remote server. Nice!

Type the following text into the window:

print "Hello there"Now save the file (either with Ctrl+S or by selecting "Save" in the File menu.) This is a very simple Python program---all it does is cause the string "Hello there" to be printed to output.

Congratulations! The file is now on the server. Now you can log into the server and run the Python program you just made. Log in using SSH and type this:

$ cd workshop

$ python hello.pyYou should see the string Hello there.

The next time you open Notepad++, it should remember your settings. Just click on the "Connect" icon again in the panel to connect to the server. You can edit other files on the server by right-clicking on the filename and selecting "Download file." (Any changes you make to this file will be saved back to the server.)

You can also use a program called nano to edit text files. The difference between nano and TextWrangler/Notepad++ is that it runs on the server, instead of running on your local machine. One advantage of this is that you don't have to go through all the weirdness of setting up a means of uploading files to the server---you just edit the files in-place. If this appeals to you, read the nano documentation here. You can edit a file on the server with nano by typing the following at the command-line prompt:

$ nano file.py... where file.py is the name of the file you want to edit.

(You might notice that while I'm editing files in class I use a text editor called vim to edit files on the server. I think vim is great but it has a very steep learning curve---teaching you how to use vim would take a whole class on its own. Read more about vim here. If you find yourself in vim and don't know how to exit, hit ESC and then type :q!.)

Okay! Now we're ready to write some actual Python programs.

So what is a program? Well, a program is a sequence of statements that we want to computer to execute, arranged in the order we want the computer to execute them.

An "expression," if you remember, is like asking the computer a question: "Computer, what's three plus five?" or "how many letters are in the word 'abcedarian'?" A "statement" is more than asking Python to answer a question: a statement asks Python to change the state of the world.

We've seen a few statements so far, such as when we've assigned values to variables in the interactive interpreter:

>>> x = 3 + 5In the above example, we've asked the computer to tell us what 3 + 5 is... but we've also asked it to do something: store that value in a variable called x.

Another example of a statement is print, which changes the state of the world by printing the value of an expression to the screen:

>>> print 3 + 5

8Again, above we've asked the computer a question (the expression 3 + 5), but we've also asked it to do something (display it to the screen).

As an example of a sequence of statements, create a new file on the server and call it "statements.py". Cut and paste this into it:

3 + 5Now upload that file to the server and run it using Python, like so:

python statements.py(Make sure you're in the same directory as the Python file when you type the above command.) What happens? Nothing! That's because we've asked Python to evaluate the statement 3 + 5... but we didn't tell it to actually do anything with that value. Open the file again and make this change:

print 3 + 5And run the script again. You should see the number 8 printed to the screen.

Open the file again and put some more statements in there:

text = "This is some text."

text_snippet = text[:-5]

print text_snippetRun the program and you should see the following output:

text.In the above example, we have some expressions (such as the expression "This is some text." which creates a string value; text:[-5] which evaluates to a slice of the named string; and text_snippet which evaluates to the string assigned to it earlier in the program) and some statements that use those expressions (assigning to the variables text and text_snippet, then printing the value in variable text_snippet).

Learning how to program Python is all about learning how to write expressions, then use those expressions in statements to make changes to the state of Python, or to display things to output.

We're going to start writing Python programs by writing programs that work a lot like UNIX command-line tools: by reading one line from input at a time, making a decision about that line or modifying that line, and then printing output back to the screen.

Here's the first program. Cut and paste it into a file called cat.py:

# our very first program

import sys

for line in sys.stdin:

line = line.strip()

print lineThis program has some boilerplate in it that I won't explain in too much detail right now, but just to give you an idea:

import sys tells Python that we want to use functions and variables defined in a "module" called sys (more about this later in the course!)for line in sys.stdin is a way of telling Python, "Hey, all the code after this line? I want to you run that code for every line that you read from standard input."# our very first program, is a "comment." A comment is a part of the program that the computer will ignore. We can use them to make notes in our program, e.g., to explain what a particular part of the program does so we can remember what we meant when we're looking at the file later. You can make comments in Python by putting the hash character (#) anywhere---any text after the hash character counts as a comment.Make sure that lines 4 and 5 (line = line.strip() and print line) are "indented" over using a tab or spaces. (You can use however many spaces you want, as long as both lines have the same number of spaces at the beginning.)

To run this program, save it, and then in your terminal window, type

$ python cat.pyType in a few lines, then hit Ctrl+D. (You may need to hit Ctrl+D more than once.) What happened?

That's right---cat.py is a very simple "clone" of the cat command-line tool in UNIX. You can use it to display the contents of a file:

$ python cat.py <sea_rose.txtThis should display the contents of sea_rose.txt.

Wait, why did we do

line = line.strip()? That's a good question! Here's an exercise: trying removing that line, and then re-running the program. You'll find that you get an extra line after each line that you print out! Weird. The reason for this is two-fold: (1) when Python reads a line in from standard input, it includes the new line character (\n) in the string; (2) the.strip()to remove whitespace (i.e., spaces, new lines, tabs) etc. from the end of the string. Good catch!

This program isn't very interest on its own. Here's how we're going to make it more interesting. Instead of just printing the value in variable line, let's write an expression on that line that evaluates to the string, but with some transformation applied.

So, for example, let's write a program that prints out only the first ten characters of each line:

import sys

for line in sys.stdin:

line = line.strip()

print line[:10]Save this modified version of the program with a different filename---experiment1.py, for example. Run this using sea_rose.txt as input, like so:

$ python experiment1.py <sea_rose.txtand you should get the following output:

SEA ROSE

Rose, hars

marred and

meagre flo

spare of l

more preci

than a wet

single on

you are ca

Stunted, w

you are fl

you are li

in the cri

that drive

Can the sp

drip such

hardened iOr, try this:

import sys

for line in sys.stdin:

line = line.strip()

print line.title().swapcase()Save this as a different file (say, experiment2.py) and run it using Python, passing sea_rose.txt as input. You should get the following output:

sEA rOSE

rOSE, hARSH rOSE,

mARRED aND wITH sTINT oF pETALS,

mEAGRE fLOWER, tHIN,

sPARE oF lEAF,

mORE pRECIOUS

tHAN a wET rOSE

sINGLE oN a sTEM --

yOU aRE cAUGHT iN tHE dRIFT.

sTUNTED, wITH sMALL lEAF,

yOU aRE fLUNG oN tHE sAND,

yOU aRE lIFTED

iN tHE cRISP sAND

tHAT dRIVES iN tHE wIND.

cAN tHE sPICE-rOSE

dRIP sUCH aCRID fRAGRANCE

hARDENED iN a lEAF?Pretty cool, huh? We can now write programs that behave like simple UNIX command-line tools that modify each line of input as it comes in. And because our programs run on the command-line, we can use pipes and redirection to combine their output! For example, we can pipe the output of running experiment1.py on sea_rose.txt so it's the input of experiment2.py like so:

$ python experiment1.py <sea_rose.tt | python experiment2.pyThe output will look like this:

sEA rOSE

rOSE, hARS

mARRED aND

mEAGRE fLO

sPARE oF l

mORE pRECI

tHAN a wET

sINGLE oN

yOU aRE cA

sTUNTED, w

yOU aRE fL

yOU aRE lI

iN tHE cRI

tHAT dRIVE

cAN tHE sP

dRIP sUCH

hARDENED iWe can also add more statements in the indented part of the code, and assign to other variables if we want. And we don't have to print the line variable if we don't want to---we can print some other expression entirely! For example, let's say we wanted to print out the first four characters of each line, followed by the last four characters, storing those portions of the string in variables. Let's try this:

import sys

for line in sys.stdin:

line = line.strip()

first_four = line[:4]

last_four = line[-4:]

print first_four + last_fourSave this as fours.py and run it on sea_rose.txt:

SEA ROSE

Roseose,

marrals,

meaghin,

spareaf,

moreious

thanrose

singm --

you ift.

Stuneaf,

you and,

you fted

in tsand

thatind.

Can rose

dripance

hardeaf?EXERCISE: Write a Python program that prints out the length of each line in the input.

EXERCISE 2: Write a Python program that prints out each line of input twice.

EXERCISE 3: Write a Python program that uses the

.replace()method to make replacements to the text on each line.

We've seen how to make a version of UNIX cat. Now let's make a Python program called simplegrep.py, which is program that works a lot like UNIX grep.

import sys

for line in sys.stdin:

line = line.strip()

if "you" in line:

print lineRun this with sea_rose.txt as input, and you'll get the following results:

you are caught in the drift.

you are flung on the sand,

you are liftedThe new thing in this program is the if statement. Here's how if works. Write if followed by an expression that evaluates to True or False, followed by a colon. Any statements that are tabbed over under the if statement will only be executed if the expression evaluates to True. That's why simplegrep.py above only printed out those three lines: it used the in operator to check to see if you was a substring of each line, and then only printed out the lines where that was the case.

You can put any expression that evaluates to True or False after the if keyword. Here's a program that only prints out lines that are at least 20 characters long:

import sys

for line in sys.stdin:

line = line.strip()

if len(line) >= 20:

print line... producing the following output:

marred and with stint of petals,

meagre flower, thin,

you are caught in the drift.

Stunted, with small leaf,

you are flung on the sand,

that drives in the wind.

drip such acrid fragranceYou can put multiple statements in the part of the code that follows the if, and the expression you print out doesn't have to be line. Here's a program that finds the first comma in each line, and then only prints out what follows the comma:

import sys

for line in sys.stdin:

line = line.strip()

space_position = line.find(" ")

if space_position != -1:

substring = line[space_position+1:]

print substringRun this with sea_rose.txt and you'll get the following output:

ROSE

harsh rose,

and with stint of petals,

flower, thin,

of leaf,

precious

a wet rose

on a stem --

are caught in the drift.

with small leaf,

are flung on the sand,

are lifted

the crisp sand

drives in the wind.

the spice-rose

such acrid fragrance

in a leaf?EXERCISE: Write a Python program that prints only the lines in input that begin with a capital letter. (Hint: use string indexes and the

.isupper()method.

You can use the else keyword to write code that will execute if the expression in an if statement evaluated to False. Here's a modified version of the length-checking program above that prints the string "LONG" if the line is longer than 20 characters, and "SHORT" otherwise:

import sys

for line in sys.stdin:

line = line.strip()

if len(line) >= 20:

print "LONG"

else:

print "SHORT"Running this with sea_rose.txt yields the following output:

SHORT

SHORT

SHORT

LONG

LONG

SHORT

SHORT

SHORT

SHORT

SHORT

LONG

SHORT

LONG

LONG

SHORT

SHORT

LONG

SHORT

SHORT

LONG

SHORT

SHORTThe elif keyword (short for "else if...") allows you to write even more sophisticated tests: if the expression in the initial if clause evaluates to False, any following elif statement will have its expression evaluated; if that expression succeeds, the statements tabbed over beneath elif will be executed. If neither the if expression nor the elif expression evaluates to True, the statements beneath the else will run.

Here's a program to illustrate, which prints different strings according to how many punctuation marks are in each line of input.

import sys

for line in sys.stdin:

line = line.strip()

punctuation = line.count(".") + line.count(",") + line.count("-") + line.count("?")

if punctuation >= 2:

print "many"

elif punctuation == 1:

print "only one"

else:

print "none :("Here's the output from sea_rose.txt:

none :(

none :(

many

only one

many

only one

none :(

none :(

none :(

many

only one

none :(

many

only one

none :(

none :(

only one

none :(

only one

none :(

only one

none :(You can actually have as many elif statements as you want, checking for many different conditional expressions.

There's much more to talk about here!